September 27, 2023

We hope you enjoy our articles. Please note, we may collect a share of sales or other compensation from the links on this page. Thank you if you use our links, we really appreciate it!

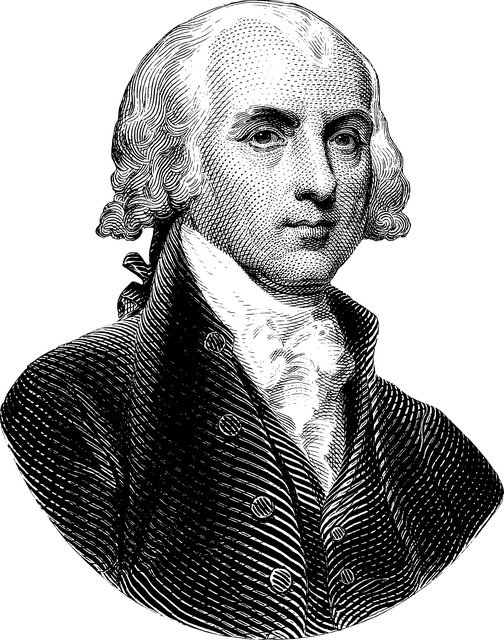

James Madison, the architect of the US Constitution, played a major role in its ratification process. He articulated his ideas in the Federalist papers, in which he tried to address the concerns of the Antifederalists on contentious issues such as division of powers between the newly formed nation and the states. Madison’s wisdom was reflected in his reconciliatory approach and moderation of extreme positions through debate and dialogue. That this Madisonian wisdom is lacking in democracies of our times is perhaps an understatement.

As reflected in the Articles of Confederation, the founding fathers, after the independence from the colonial yoke, preferred a weak national government. But in its brief existence, the confederation proved a toothless tiger as it lacked, for example, the power of taxation and the power to check armed rebellion. The founding fathers decided to address this weakness and convened in Philadelphia to draft the constitution. The process of ratification of the constitution was not easy and it was the genius of Madison – willingness to accommodate the demands of the opposition, for example drafting Bill of Rights to address the concerns of Antifederalists, exploring a middle path through debate and dialogue – that played a major role in the ratification of the constitution.

Madison was influenced by the Greek and Enlightenment Philosophy. Federalist Paper 49 used the terms ‘enlightened reason’ and ‘nation of philosophers,’ reflecting the influence of Greek philosopher, Plato. Federalist paper 51 made a pertinent observation on human nature and argued for rule of law, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.” It added, “In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

One of the challenges before Madison, hence, was how to checkmate human passion and selfishness, and let it be governed by higher reason that puts the country before the narrow individual interests. Madison argued, when people are virtuous, disciplined, and guided by ‘enlightened reason’ strict rules and regulations are not necessary. But the pragmatist in him reasoned that as such an ideal scenario is not possible, it is necessary to establish rule of law. But Madison’s pragmatism was suffused with optimism that the Americans would carry on and strengthen the democratic republican vision that guided the founding of the constitution. That was one of the reasons why the founding fathers did not put everything in writing in the constitution and produced a small, but powerful, document (unlike constitutions in some other countries, which run into hundreds of pages). As articulated by historian David McCullough, the founding fathers – neither perfect themselves, nor creators of a perfect democratic system – were guided by the vision that the democratic republic they were founding would evolve with passing decades as, in its core, it is guided by ‘enlightened reason’.

Madison spent considerable energy in addressing the Antifederalist concern that a strong nation would usurp powers of the states and result in tyranny. While elaborating on it in one of his complex writings, Federalist Paper 39, he adopted a middle path. He wrote, “The proposed Constitution, therefore, is, in strictness, neither a national nor a federal Constitution, but a composition of both. In its foundation it is federal, not national; in the sources from which the ordinary powers of the government are drawn, it is partly federal and partly national; in the operation of these powers, it is national, not federal; in the extent of them, again, it is federal, not national; and, finally, in the authoritative mode of introducing amendments, it is neither wholly federal nor wholly national.” Here Madison developed the concept of shared sovereignty, implying neither the national government nor the state governments are absolutely sovereign (which traditionally places sovereignty, or legitimate right to rule, in one center of power), but they share power depending on the context and circumstances.

For Madison, the foundation of the nation is federal, implying the states laid the foundation of the nation. The original founding states preceded their creation – the nation. Also, for him, the powers of the government were both federal and national – in this context one could think of members of House of Representatives being directly elected by the people, and Senators elected by the state legislatures (after the passing of the 17th amendment in 1913 they were elected directly by the people). Another example he provided was the constitutional amendment process in which both the national government and states played roles. For Madison, the American democratic political system embodied a combination of national sovereignty and state sovereignty in reciprocal, and harmonious, ways, keeping in view the best interests of the people, the states and the nation.

The Madisonian reconciliatory vision led the evolution of the US as one of the most powerful and pluralistic democracies in the world despite myriad challenges in the past two centuries. Madison’s reconciling vision played a role in this process, and he himself, as a founder and leader of the nation, exemplified this vision in his public life. Madisonian path of dialogue and collaboration and his vision of a democratic republican government led by leaders of ‘enlightened reason’ need to be explored to address our contemporary crises.

(A modified version of the article was published in Florida Times-Union on September 10, 2023.)