October 17, 2023

We hope you enjoy our articles. Please note, we may collect a share of sales or other compensation from the links on this page. Thank you if you use our links, we really appreciate it!

A young man in Jacksonville, who once aspired to be a business administrator, turned out to be a madman. He went to a variety store and killed people because they had a different skin color. Gov. Ron DeSantis later used the word “madman” to describe this person, and Sheriff T.K. Waters referred to his hate-filled writings as “the diary of a madman.”

For conflict transformation, it is not helpful to blame a particular group or community for this act by one individual. It is also not helpful to blame political ideologies for such horrible incidents — for an effective democracy, competitive political parties representing people’s demands are needed.

But the larger questions remain unanswered. What are the factors that turned this aspiring businessman into a killer? How does society play a role in producing such disturbed individuals?

Moral exclusion theory tells us that once an individual or group is excluded from one’s ethical world, they are subject to violence without remorse. It is like killing a venomous snake or a man-eating alligator and feeling no sorrow. The basis of exclusion can be anything — race, religion, culture, nationality or something else.

A Harvard University study in 2014, on select commuter rail platforms in Boston, found that the more people with different backgrounds interact, the more they tend to socially accept each other. More interaction lessens the scope of moral exclusion.

That is the basic idea of social capital ― people’s interactions in social spaces promote intercultural understanding and minimize the scope for hostility or violence.

Community interactions, however, are increasingly smothered in this social media age. Social media, which is supposed to bring people closer in a virtual world, has apparently distanced people and solidified their differences, amplifying deep cultural fault lines. It has emerged as a place of hatred and unfounded theories that pit communities against each other.

It is no surprise that many “madmen” are groomed in social media.

No single ideology or belief can be the sole catalyst for such incidents. The politics of democracy are based on healthy competition of political visions and plans of action. But when democracy turns into demagoguery, the results are undemocratic.

In his 1796 farewell address, George Washington referred to the detestable “spirit of party” as it “agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection.” Short-sighted political statements can work as catalysts to mobilize members of a group, heightened by moral exclusion, to target members who do not belong to their group.

As the sociocultural divisions are deeper, the search for a peaceful community must also go deeper and transcend the binary dynamics of oppressor-oppressed, victor-victim and majority-minority. It is not about an individual or a single community; it is about the whole social fabric, in which each fiber is deliberately cultivating empathy and developing a habit for peaceful change.

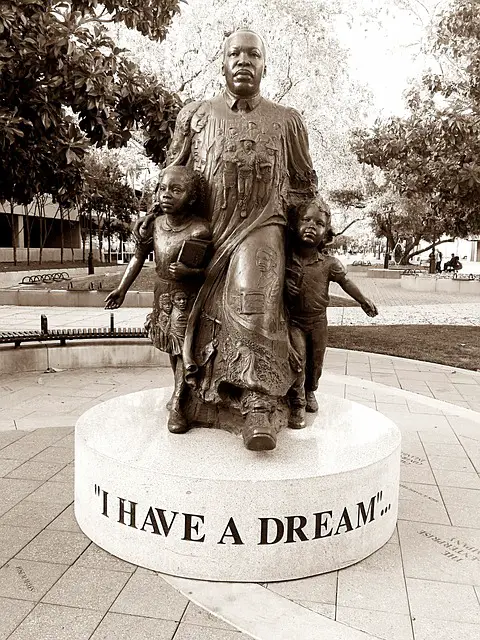

The example of Nelson Mandela of South Africa comes to mind. After being elected as leader of the independent nation, Mandela forgave apartheid-era rulers. He conceived a “rainbow nation” that accommodated competing voices. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission played a major role in bringing communities together in South Africa.

Forgiveness, however, does not mean that the victims of injustice will remain so perpetually, despite their forgiving nature.

Mahatma Gandhi led the nonviolent struggle against British rule in India and argued, “there is no path to peace. Peace is the path.” Peace and empathy go together as a peaceful society is founded on a bedrock of empathy, which cannot be cultivated without peace at the very core of thinking and action. Gandhi influenced leaders including Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Martin Luther King Jr., Mandela and many others who led nonviolent movements.

Bonhoeffer wrote to Gandhi in 1934, “The great need of Europe and Germany in particular is not the economic and political confusion, but it is a deep spiritual need … if not all signs deceive us, everything seems to work for war in the near future, and the next war will certainly bring spiritual death of Europe.”

Though Bonhoeffer wrote these words almost 90 years ago, they aptly reflect the current sociopolitical situation. States all over the world are suffering from a spiritual crisis, as articulated by Bonhoeffer, though to varying degrees.

The Bible teaches, “love thy neighbor as thyself.” This is love that transcends narrow constructions, manifested in othering and the violent clash of identities. To cultivate this love in daily life and action is not a contingent need but, to use Bonhoeffer’s words, a “deep spiritual need.”

Perhaps there is no other way to envision a peaceful society.

(A modified version of the article was published in Florida Times-Union, on October 15, 2023.)